In the last issue, Spartak associates drove praetor armies in southern Italy and increased their numbers by freeing up slaves and recruiting a variety of outcasts, which were in short supply both in cities and on the highway.

In the Senate, the gladiators were greatly offended and decided to raise rates by throwing two consuls with four legions on the table - about 30 thousand people. Spartacus, by the way, had much more by that time, but who, being in his mind, compares the iron Roman cohorts with any rabble?

Before the Thracian, the Republic had already dealt with two revolts of slaves, and some even managed to defeat the praetor armies, who understood the old way from whom, but when regular units came in, the thick polar fox quickly came to the rebels with an elegant gait. This time, the Senate was hoping for the same outcome.

Having wintered in the south and pulling up his troops to the level where it was possible to look at them, without risking breaking his whole face with feispalms, Spartak led them north to the side of Gaul. At the same time, on the way from the main army, a detachment under the leadership of Crixus separated, comprising, according to various sources, about 20-30 thousand people. Historians have different opinions about such a deviation from the route - some believe that it was a very cunning plan with an "ambush detachment", which at the right time should have been famously drawn in the rear of the punitive legions or to meet the retreating, others think that Spartak Crixus did not agree on the issue of the final point of the route. Say, the Thracian wanted to go to Gaul for free bread, and his comrade believed that savages with property were hard and when robbed instead of valuables, they could only get there on the head, so I wanted to go to Rome.

In any case, Crixus climbed from old memory onto Mount Monte Gargano, which is located on the peninsula of the same name (the same “spur” on the Italian “boot”). Spartak, meanwhile, very successfully met the legions of one of the consuls who did not have time to get into combat readiness - they had just come down from the mountains, overcoming the Apennines, and taking advantage of such a convenient opportunity, defeated them, although not completely, but backtracked on Roman convoys.

His comrade on the mountain was less fortunate - by the time the legions of the other consul got to her, they were already quite ready to tear and throw, which, in fact, was done with Crixus. He, like most of his squad, did not survive this battle.

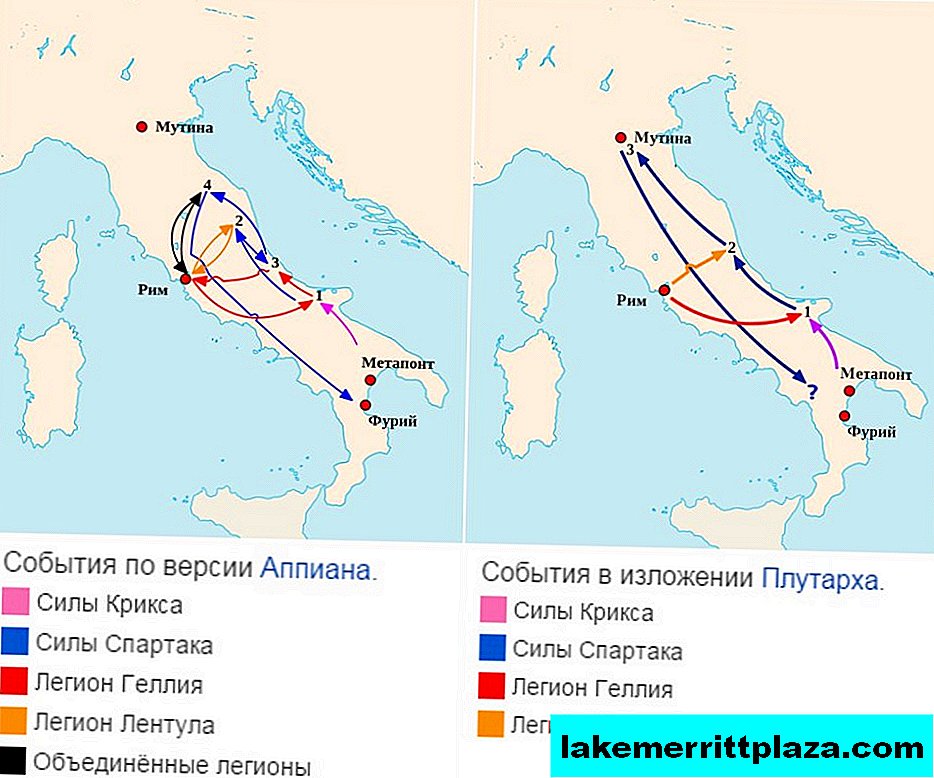

In the description of further events, the main historical versions of Appian and Plutarch diverge and tell of different things. First, we retell the first hypothesis.

According to her, the consuls tried to drag Spartak’s army into ticks: one was waiting for the gladiator in the north of the road towards Gaul, the second was quickly catching up from the south. Since Italy is still a mountainous side and large crowds there is not much to turn around, and the Romans built their roads for a long time, the approximate route of the movement of the slave crowd was clear. However, Spartak, realizing that it was impossible to procrastinate in any case, threw the excess from the loot, stabbed the slow captives, gave everyone knowing how to strengthen turpentine and drowned it in such a way that he managed to smash the enemy in the north, and then turn around and joyfully meet the attackers from the south.

After this, the Thracian drove the enemy to Rome, but did not try to take the Eternal City, since he was somewhat more sober in assessing his strength than the late Crixus. Instead, he once again, for an encore, defeated the consular armies, which were somehow understaffed, and returned to the south, to warm and settled places, forging weapons, robbing the undercut and living for his own pleasure.

Plutarch writes only about the battle of Spartacus with the first consul, after which the former slave sprinkles a sprightly march right up to the very north of Italy, the city of Mutina (present Modena). Having defeated a local army of tens of thousands of people there, the gladiator suddenly got bored, got a bit of a hand, and wandered back south. Either the Alps decided not to storm without cats and ice axes, or it froze - it is unclear, and Plutarch does not explain such sharp movements in any way. According to his description, Spartacus replenished the army with slaves in the north, and after, having passed by Rome screaming in a panic, he returned to the south.

In any case, the sources converge in the main outline of events - the consular legions were not mastered, and the slaves, having twirled a little and twirled around the capital, came from where they started.

In Rome they became completely worried and assigned the uprising the highest category of danger and urgency. At the same time, all really sensible commanders and strategists were already occupied, and far away: Lucullus, as it was written before, butted with Mithridates, and Gnei Pompey fiercely chopped up in Spain with the Roman separatists and the local who joined them. Of course, both were invited to participate in forcing slaves to peace, but until the mail arrives, until they can transfer control to someone else, until they get there, Spartak will already fervently jump on Capitol Hill.

Therefore, when Mark Licinius Crassus, a millionaire, “philanthropist” and longtime opponent of Pompey, volunteered to solve the problem once and for all, the Senate had nothing to object to.

On the actions of Crassus - in the next issue.

Based on materials from History Fun.